A forgotten East Indian leader & Tilak’s aide is resurrected this election

Joseph Baptista was a London-educated barrister, father of Home Rule movement and thefirst Indian-origin mayor of Bombay.

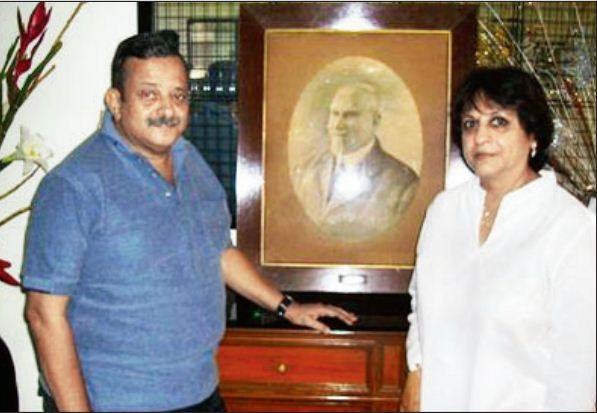

Trevor D’Silva and Joan Saint-Prix with the portrait of their great granduncle

Baptista came from a well-placed family. He had a good education and started out as an engineer in the Forest department, says writer Neville Gomes. It was Dadabhai Naoroji who spotted his talent for oration and leadership and urged him to set sail for England to study politics and qualify for the Bar. “From what I have seen and researched, Baptista earned his spurs through various interactions, impressing leading lights like Lord Montague and building contacts in the British Labour Party,” says Gomes, who wrote about him in ‘Viva Queimada’.

Baptista had the ability to make the best of his advantages. When he returned, he used insights from England to galvanise labour as a pressure group, won the support of postal workers, mill hands and coal miners. “It is significant that the AITUC of which he was a co-founder rattled up a membership of over 50 unions and 1.5 lakh workers,” says Gomes. Apart from transplanting ‘Home Rule’ from Irish nationalists, Gomes believes it was Baptista who put out the idea of ‘Freedom is My Birthright’. “His writings show that he was imaginative and had a powerful pen. Tilak probably jumped at the concept and reinforced it with his own version of ‘Swarajya mazha janmasiddha hakka ahay’,” says Gomes.

The two men worked closely and that is why Tilak insisted on Baptista handling his defense in 1907 when he was prosecuted for sedition. Baptista also initiated the reform to give tax-paying tenants the right to vote in Bombay municipal elections.

Baptista remained genuinely interested in the plight of workers who called him ‘Kaka’. Single and cosmopolitan, he was also a master of witty repartees. As an articulate Cambridge undergraduate, he once addressed an election rally in York. The candidate he supported had incurred the wrath of employees due to his membership of the employers’ federation. Baptista was howled down: “Shut up, black man, shut up.” “Better a black man than a blackguard,” he retorted to applause and roars of laughter, writes Times.

Much of this history remains forgotten, some say even by the community. “When my father (K R Shirsat) was writing a book in the 1970s, he asked for information but didn’t get any. Some questioned what Baptista had done for the community,” says Ravi Shirsat, who runs the Joseph Baptista Institute of Politics and Economics in Vasai.

Gomes says that Baptista disagreed with the community at times and advised them to graft into the mainstream, as he knew it was too small on its own. When he died, mourners like Dr D A D’monte say how “his (Baptista’s) friends knew that he was a man of Hindustan, a typical Maratha, and that this meant (he was) too large to be limited to his immediate surroundings,” writes Times.

All that seems to be changing. Last year, Shirsat’s trust and the Panchayat celebrated his 150th birth anniversary. Family and residents at Matharpacady, where the leader’s home had long been ‘redeveloped’, are cautiously optimistic. Even this effort might not be enough, says Gomes. “The community has morphed into a larger universe through inter-marriage and migration. We need a dozen Kakas to drive people into the mainstream and become a power group,” he says.